West Papua (region)

- This article is about the Indonesian western half of the island of New Guinea. For the Indonesian province, see West Papua (province).

| Papua | |

|---|---|

| Region | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Cities | Jayapura, Manokwari, Sorong, Timika, Fak Fak |

| Provinces |

2

|

| Area | 420,540 km² (162,371 sq mi) |

| Highest point | Puncak Jaya |

| - location | Sudirman Range |

| - coordinates | |

| - elevation | 4,884 m (16,024 ft) |

| Population | 2,646,489 (2005) |

| Density | 6 / km² (16 / sq mi) |

| Time zone | WIT (UTC+9) |

| ISO 3166-2 | ID-IJ |

| License plate | DS |

|

|

West Papua refers to the Indonesian western half of the island of New Guinea and other smaller islands to its west. The eastern half of the island is Papua New Guinea.

The population of approximately 3 million comprises indigenous ethnic Papuans, Melanesians, and Austronesians (largely immigrants from other Indonesian areas). The region is predominantly dense forest where numerous traditional tribes live such as the Dani of the Baliem Valley, although the majority of the population live in or near coastal areas. The largest city in the region is Jayapura. The official and most commonly spoken language is Indonesian. Estimates of the number of tribal languages in the region range from 200 to over 700, with the most widely spoken including Dani, Yali, Ekari and Biak. The predominant religion is Christianity (often combined with traditional beliefs) followed by Islam. The main industries include agriculture, fishing, oil production, and mining.

Human habitation is estimated to have begun between 42,000 and 48,000 years ago.[1] The Netherlands made claim to the region and commenced missionary work in nineteenth century. The region was incorporated into the Indonesian republic in the 1960s, which remains controversial with much of the territory's indigenous population, West Papuan nationalist organisations, and some international NGOs and advocates of West Papua self-determination.[2] Following the 1998 commencement of reforms across Indonesia, Papua and other Indonesian provinces received greater regional autonomy. In 2001, "Special Autonomy" status was granted to West Papua, although to date, implementation has been partial.[3] The region was divided into the provinces of Papua and West Papua in 2003.

The region has also been called Netherlands New Guinea (1895–1962), West New Guinea (1962–63), West Irian (1963–73), Irian Jaya (1973–2001), and Papua (2002–2003). West Papua is the name preferred by indigenous Papuans.[4]

Contents |

Geography

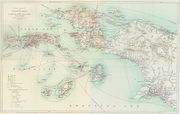

The region is 1,200 km from east to west and 736 km north to south. It has an area of 420,540 km2 (162,371 sq mi), approximately 22% of Indonesia's land area. The border with Papua New Guinea mostly follows the 141st meridian east, with one section defined by the Fly River.

The island of New Guinea was once part of the Australian landmass and lie on the Sahul. The collision between the Indo-Australian Plate and Pacific plate resulting in the Maoke Mountains run through the centre of the region and are 600 km (373 mi) long and 100 km (62 mi) across. The range includes about ten peaks over 4,000 metres (13,120 feet) including,[5] Puncak Jaya (4,884 m), Puncak Trikora (4,750 m), and Puncak Mandala (4,701 m). The range ensures a steady supply of rain from the tropical atmosphere. The tree line is around 4,000 m (13,100 ft) and the tallest peaks feature small glaciers and are snowbound year round. Both north and west of the central ranges the land remains mountainous — mostly 1,000 to 2,000 m (3,300–6,660 ft) high with a warm humid climate year round. The highland areas feature alpine grasslands, jagged bare peaks, montane forests, rainforests, fast flowing rivers, and gorges. Swamps and low-lying alluvial plains of fertile soil dominate the southeastern section around the town of Merauke. Swamps also extend 300 km around the Asmat region.

The province has 40 major rivers, 12 lakes, and 40 islands. The Mamberamo river is the province's largest river which winds through the northern part of the province. The result is a large area of lakes and rivers known as the Lakes Plains region. The vast southern lowlands, which consist of a mosaic of habitats including mangrove, tidal and freshwater swamp forest and lowland rainforest, are home to a dense population of fishermen and gatherers such as the Asmat people. The Baliem Valley, home of the Dani people is a tableland 1,600 m (5,250 ft) above sea level in the midst of the central mountain range.

The dry season across the region is generally between May and October; although drier in these months, rain does persists throughout the year. Strong winds and rain are experienced along the north coast in November through to March. However, the south coast experiences and increase in wind and rain between April and October, which is the dry season in the Merauke area, the only part of West Papua to experience distinct seasons. Coastal areas are generally hot and humid, whereas the highland areas tend to be cooler.

Ecology

Lying in the Asia-Australian transition zone near Wallacea, the regions flora and fauna include Asiatic, Australian, and endemic spieces.

Marsupial spieces dominate and the region; there are an estimated 70 marsupial spieces (including possums, wallabies, tree-kangaroos, cuscus), and 180 other mammal spieces (including the endangered long-beaked echidna). The region is the only part of Indonesia to have kangaroos, marsupial mice, bandicoots, and ring-tailed possums. The approximately 700 bird species include cassowaries (along the southern coastal areas), bowerbirds, kingfishers, crowned pigeons, parrots, cockatoos) of which 450 are endemic. Birds of paradise can be found in Kepala Burung and Yapen. The region is also home to around 800 spieces of spiders, 200 frogs, 30,000 beetles, 70 bat spieces, the world's longest lizards (Papua monitor) and some of the world's largest butterflies. The extensive waterways and wetlands of Papua are also home to salt and freshwater crocodile, tree monitor, flying foxes, osprey. and other animals; while the equatorial glacier fields remain largely unexplored.

The region is 75% forest and it has a high degree of biodiversity. The island has an estimated 16,000 species of plant, 124 genera of which are endemic. The mountainous areas and the north are covered with dense rainforest. Highland vegetation also includes alpine grasslands, heath, pine forests, bush and scrub. The vegetation of the south coast includes mangroves and sago palms, and in the drier southeastern section, eucalypts, paperbarks, and acacias.

In February 2005, a team of scientists exploring the Foja Mountains discovered numerous new species of birds, butterflies, amphibians, and plants, including a species of rhododendron which may have the largest bloom of the genus.[6]

Environmental issues include deforestation, the spread of the introduced Crab-eating Macaque which now threatens the existence of many native monkey species, and discarded copper and gold tailings from the Grasberg mine.[7]

Demographics

The population of the region was estimated to be 2,646,489 in 2005. The interior is predominantly populated by ethnic Papuans and coastal towns are inhabited by descendants of intermarriages between Papuans, Melanesians, and Indonesians. Migrants from the rest of Indonesia, including those from the government Transmigrasi programs also tend to inhabit the coastal regions. The two largest cities in the territory are Sorong in the northwest of the Bird's Head Peninsula and Jayapura in the northeast. Both cities have a population of approximately 200,000.

The region is home to around 312 different tribes, including some uncontacted peoples.[8] The Dani, from the Baliem Valley, are one of the most populous tribes of the region. The Manikom and Hatam inhabit the Anggi Lakes area, and the Kanum and Marind are from near Merauke. The semi-nomadic Asmat inhabit the mangrove and tidal river areas near Agats and are renowned for their woodcarving. Other tribes include the Amungme, Bauzi, Biak (Byak), Korowai, Lani, Mee, Mek, Sawi, and Yali. Estimates of the number of distinct languages spoken in the region range from 200 to 700. A number of these languages are permanently disappearing.

As in Papua New Guinea and some surrounding east Indonesian provinces, a large majority of the population is Christian. In the 2000 census 54% of West Papuans identified themselves as Protestant, 24% as Catholic, 21% as Muslim, and less than 1% as either Hindu or Buddhist. There is also substantial practice of animism among the major religions, but this is not recorded by the census.

Haplogroups

There are 6 main Y-chromosome haplogroups in West Papua; Y-chromosome haplogroup M is the most common, with Y-chromosome haplogroup O2a as a small minority in second place and Y-chromosome haplogroup S back in third position across the mountain highlands; while D, C2 and C4 are of negligible numbers.

- Haplogroup M is the most frequently occurring Y-chromosome haplogroup in West Papua.[9]

- In a 2005 study of Papua New Guinea’s ASPM gene variants, Mekel-Bobrov et al. found that the Papuan people have among the highest rate of the newly-evolved ASPM haplogroup D, at 59.4% occurrence of the approximately 6,000-year-old allele.[10]

- Haplogroup O2a (M95) is typical of Austro-Asiatic peoples, Kradai peoples, Malays, Indonesians, and Malagasy, with a moderate distribution throughout South, Southeast, East, and Central Asia.

- Haplogroup S occurs in eastern Indonesia (10–20%) and Island Melanesia (~10%), but reaches greatest frequency in the highlands of Papua New Guinea (52%).[11]

Culture

West Papuans have significant cultural affinities with the inhabitants of Papua New Guinea. As in Papua New Guinea the peoples of the highlands have distinct traditions and languages from peoples of the coast, though Papuan scholars and activists have recently detailed cultural links between coast and highlands as evidenced by close similarity of family names.

Some Papuans fear that the history of Indonesian governance, education, propaganda, and immigration have undermined Papuan cultures. In March 2003, human rights activist John Rumbiak said that Papuan culture will be "extinct" within 10 to 20 years, if the present rate of assimilation in the region continues.[12] In response to such criticism the Indonesian government states that the special autonomy arrangement specifically addresses the ongoing preservation of Papua culture, and that the transmigration program was "designed specifically to help the locals through knowledge transfer."[13]

In some parts of the highlands, the koteka (penis gourd) is worn by males in ceremonial contexts. Despite government efforts to suppress it in the early 1970s, the use of the koteka as everyday dress by Dani males in Western New Guinea is still common.

History

Pre-colonial history

Papuan habitation of the region is estimated to have begun between 42,000 and 48,000 years ago.[1] Austronesian peoples migrating through Maritime Southeast Asia settled several thousand years. These groups have developed diverse cultures and languages in situ; there are over 300 languages and two hundred additional dialects in the region (See Papuan languages, Austronesian languages).

On 13 June 1545, Ortiz de Retez, in command of the San Juan, left port in Tidore, an island of the East Indies and sailed to reach the northern coast of the island of New Guinea, which he ventured along as far as the mouth of the Mamberamo River. He took possession of the land for the Spanish Crown, in the process giving the island the name by which it is known today. He called it Nueva Guinea owing to the resemblance of the local inhabitants to the peoples of the Guinea coast in West Africa.

Netherlands New Guinea

In 1660, the Dutch recognised the Sultan of Tidore's sovereignty over New Guinea. New Guinea thus became notionally Dutch as the Dutch held power over Tidore. In 1793, Britain attempted to establish a settlement near Manokwari, however, it failed and by 1824 Britain and the Netherlands agreed that the western half of the island would become part of the Dutch East Indies. In 1828 the Dutch established a settlement in Lobo (near Kaimana) which also failed. Almost 30 years later, Germans established the first missionary settlement on an island near Manokwari. While in 1828 the Dutch claimed the south coast west of the 141st meridian and the north coast west of Humboldt Bay in 1848, they did not try to develop the region again until 1896; they established settlements in Manokwari and Fak-Fak in response to perceived Australian ownership claims from the eastern half of New Guinea. Great Britain and Germany had recognised the Dutch claims in treaties of 1885 and 1895. At much the same time, Britain claimed south-east New Guinea, later known as the Territory of Papua, and Germany claimed the northeast, later known as the Territory of New Guinea.

Dutch activity in the region remained in the first half of the twentieth century, not withstanding the 1923 establishment of the Nieuw Guinea Beweging (New Guinea Movement) in the Netherlands by ultra right-wing supporters calling for Dutchmen to create a tropical Netherlands in Papua. This prewar movement without full government support was largely unsuccessful in its drive, but did coincide with the development of a plan for Eurasian settlement of the Dutch Indies to establish Dutch farms in northern West New Guinea. This effort also failed as most returned to Java disillusioned, and by 1938 just 50 settlers remained near Hollandia and 258 in Manokwari. The Dutch established the Boven Digul camp in Tanahmerah, in Dutch New Guinea, as a prison for Indonesian nationalists.

In the early 1930s, the need for a national Papuan government was discussed by graduates of the Dutch Protestant Missionary Teachers College in Mei Wondama, Manokwari. These graduates continued their discussions among the wider community and quickly succeeded in cultivating a desire for national unity across the region and its three hundred languages. The College Principal Rev. Kijne also composed "Hai Tanahku Papua" ("Oh My Land Papua"), which in 1961 was adopted as the national anthem. A exploration company NNGPM was formed in 1935 by Shell (40%), Mobil (40%) and Chevron's Far Pacific investments (20%) to explore West New Guinea. During 1936, Jean Dozy working for NNGPM reported the world's richest gold and copper deposits in a mountain near Timika which he named Ertsberg (Mountain of Ore). Unable to license the find from the Dutch or indigenous landowners, NNGPM maintained secrecy of the discovery.

World War II

The region became important in the War in the Pacific upon the Netherland's declaration of war on Japan after the bombing of Pearl Harbour. In 1942, the northern coast of West New Guinea and the nearby islands were occupied by Japan.

In 1944, forces led by American general Douglas MacArthur launched a four-phase campaign from neighbouring Papua New Guinea to liberate Dutch New Guinea from the Japanese. Phase 1 was the capture of Hollandia (now Jayapura). Involving 80,000 Allied troops it was the largest amphibious operation of the war in the southwest Pacific. Phase 2 was the capture of Sarmi and was met with strong Japanese resistance. The capture of Biak to control the airfield and nearby Numfor was Phase 3. Hard battles were fought on Biak which was exacerbated by Allied intelligence underestimating the strength of Japanese forces. The fourth and final phase was the push to Japanese airbases on Morotai and towards the Philippines. The Allies also fought for control of Merauke as they feared it could be used as a base for Japanese air attacks against Australia.

With Papuan approval, the United States constructed a headquarters for Gen. Douglas MacArthur at Hollandia (now Jayapura) and over twenty US bases and hospitals intended as a staging point for operations taking of the Philippines. West New Guinean farms supplied food for the half million US troops. Papuan men went into battle to carry the wounded, acted as guides and translators, and provided a range of services, from construction work and carpentry to serving as machine shop workers and mechanics.

Following the end of the war, the Dutch retained possession of West New Guinea from 1945.

Indonesian independence

Since before the Japanese occupation in World War II, many Indonesian nationalists, including Sukarno, had imagined an Indonesia based on a Muslim-Malay race identity that included British Malaya, north Borneo, and Portuguese Timor. However, the post World War II deployment of Allied troops meant that an Indonesia based on former Dutch colonial possessions including western New Guinea, became the accepted goal of Indonesian nationalists. Upon the Japanese surrender in the Pacific, Indonesian nationalists declared Indonesian independence and claimed all Dutch possessions, including western New Guinea, as part of the Republic of Indonesia. A four & half year diplomatic and armed struggle ensued between the Dutch and Indonesian republicans. It ended in December 1949 with the Netherlands recognising Indonesian sovereignty over the Dutch East Indies with the exception of Dutch New Guinea. Unable to reach a compromise on the region, the conference closed with the parties agreeing to discuss the issue within one year.

In December 1950[14] the United Nations requested the Special Committee on Decolonization to accept transmission of information regarding the territory in accord with Article 73 of the Charter of the United Nations. After repeated Indonesian claims to possession of Dutch New Guinea, the Netherlands invited Indonesia to present its claim before an International Court of Law. Indonesia declined the offer. In attempt to prevent Indonesia taking control of the region, the Dutch significantly raised development spending off its low base,[15] and encouraged Papuan nationalism. They began building schools and colleges to train professional skills with the aim of preparing them for self-rule by 1970. A naval academy was opened in 1956, and Papuan troops and naval cadets began service by 1957. A small western elite developed with a growing political awareness attuned to the idea of independence and close links to neighbouring eastern New Guinea which was administered by Australia.[16] Local Council elections were held and Papuan representatives elected from 1955.

On 6 March 1959 the New York Times published an article revealing the Dutch government had discovered alluvial gold flowing into the Arafura Sea and were searching for the gold's mountain source. In 1959, Freeport Sulphur approached the Dutch East Borneo company for partnership. An agreement signed in January 1960 to lodge a Dutch claim for the Timika area as a copper deposit did not inform the government about the gold or known extent of the copper deposit.

Election of a national parliament began on 9 January 1961 in fifteen electoral districts with direct voting in Manokwari and Hollandia to select 26 Councillors, of whom 16 were elected, 12 appointed, 23 were Papuan, and one female Councillors. The Councillors were sworn in by Governor Platteel on 1 April 1961, and the Council took office on 5 April 1961. The inauguration was attended by officials from Australia, Britain, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and members of the South Pacific Commission; a large Australian delegation was headed by Mr Hasluck MP and included Sir Alistair McMullan, President of Australian Senate. The United States declined the invitation to attend the inauguration.

After news that the Hague was considering a United States plan to trade the territory to United Nations administration, Papuan Councillors met for six hours in the New Guinea Council building on 19 October 1961 to elect a National Committee which drafted a Manifesto for Independence & Self-government, a National flag (Morning Star), State Seal, selected a national anthem ("Hai Tanahkoe Papua" / "Oh My Land Papua"), and called for the people to be known as Papuans. The New Guinea Council voted unanimous support of these proposals on 30 October 1961, and on 31 October 1961 presented the Morning Star flag and Manifesto to Governor Platteel who said (translated) "Never before has the oneness of the Council been put forward so strongly." The Dutch recognized the flag and anthem on 18 November 1961 (Government Gazettes of Dutch New Guinea Nos. 68 and 69), and these ordinances came into effect on 1 December 1961.

The Morning Star flag was raised next to the Dutch tricolour on 1 December 1961, an act which Papuan independence supporters celebrate each year at flag raising ceremonies. National Committee Chairman Mr Inury said: "My Dear compatriots, you are looking at the symbol of our unity and our desire to take our place among the nations of the world. As long as we are not really united we shall not be free. To be united means to work hard for the good of our country, now, until the day that we shall be independent, and further from that day on."

Incorporation into Indonesia

Sukarno made a take over of western New Guinea a focus of his continuing struggle against Dutch imperialism and part of a broader Third World conflict with the West.[17] Both of Sukarno's key pillars of support, the Indonesian Communist Party and Indonesian army supported his expansionism.[18] In December 1961, President Sukarno created a Supreme Operations Command for the "liberation of Irian". In January 1962, Suharto, recently promoted to major General, was appointed to lead Operation Mandala, a joint army-navy-air force command. This formed the military side of the Indonesian campaign to win the territory, from the Dutch who were preparing it for its own independence, separate from Indonesia.[19] Indonesian forces had previously infiltrated the territory using small boats from nearby islands. Operations Pasukan Gerilya 100 (November 1960) and Pasukan Gerilya 200 (September 1961), were followed around the time of Suharto's appointment by Pasukan Gerilya 300 with 115 troops leaving Jakarta on four Jaguar class torpedo boats (15 January). They were intercepted in the Aru Sea and the lead boat was sunk. 51 survivors were picked up after flotilla commander Commodore Yos Sudarso went down with his boat.[20] Parachute drops were made onto the swampy south coast away from the main concentration of Dutch forces. The commandos were thwarted by tall trees on which they were snared and by the swampy terrain which made them wet and ill, and their equipment was lost and damaged. Having been prepared for eventual independence by the Dutch, the Papuan population did not welcome the Indonesians as liberators. For the most part, Papuans attacked the paratroopers or handed them over to Dutch authorities. Of the 1,429 troops dropped into the region, 216 were killed or never found, and 296 were captured.[21]

While Dutch casualties were relatively few, they knew that a military campaign to retain the region would require protracted jungle warfare. Unwilling to repeat the events of 1945-1949, the Dutch agreed to American mediation. Supporting the secret talks was the new American President, John F Kennedy, who said that compromise "will inevitably be unsatisfactory in some degree to both sides (indeed we have deliberately let ourselves be placed in this exposed position to give both sides someone else to blame)". Kennedy took the advice of American ambassador to Indonesia, Howard Jones, and that of his own National Security Council, which was counter to the views of the Dutch and the CIA. With continuing Indonesian military pressure, Kennedy sent his brother, Robert, to Jakarta to solicit entry into negotiations without pre-conditions. Sukarno had hinted at releasing Allen Pope sentenced to death for bombing Ambon four years previously, however, he now offered to release Pope in exchange for America's support against the Dutch.

In July 1962, Suharto's Mandala Command was preparing to resolve the military campaign with a major combined air and sea assault on the trade and communications centre of Biak Island, which was the location of a Dutch military base and the only jet airstrip.[21][22] However, this risky operation did not eventuate as continuing US efforts to have the Netherlands secretly negotiate the transfer of the territory to Indonesian administration succeeded in creating the "New York Agreement", which was signed on 15 August 1962.[21] The Australian government, which had previously supported of Papuan independence, also reversed its policy to support incorporation with Indonesia.[23][24]

The vaguely-worded agreement, ratified in the UN on 21 September 1962, required authority to be transferred to a United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA) on 1 October 1962, and that once UNTEA had informed the public of the terms of the Agreement, administration of the territory would transfer to Indonesia after 1 May 1963, until such time as Indonesia allowed the Papuans to determine whether they wanted independence or be part of Indonesia. On 1 May 1963, UNTEA transferred total administration of West New Guinea to the Republic of Indonesia. The capital Hollandia was renamed Kota Baru for the transfer to Indonesian administration and on 5 September 1963, West Irian was declared a "quarantine territory" with Foreign Minister Subandrio administrating visitor permits.

In 1969, the United Nations supervised the "Act of Free Choice" in which the Indonesian government used the procedure of musyawarah, a consensus of 'elders'. With Papuan nationalism not yet sufficient enough to contest the "consensual" ritual,[25] a unanimous vote for integration was reached amongst the 1,054 representatives chosen from Merauke, Jayawijaya and Paniai districts. Many of the chosen voters allege they were threatened and blackmailed to ensure a pro-Indonesian outcome. Soon after, the region was renamed, "West Irian", and became the 26th province of Indonesia.

West Papua within Indonesia

The Free Papua Movement (OPM) engaged in a small-scale conflict with the Indonesian military. A human-rights advocate alleges documentation of 921 deaths from military operations in the region between 1965 and 1999.[26] Seeking money and international recognition, OPM held thirteen scientists and others conducting highland forestry research hostage for 4 months in 1996. After failed negotiations with the International Commitee of the Red Cross failed, Suharto's son-in-law, Prabowo, rescued the hostages with numerous deaths.[26] Local and international protest followed the impact of economic development and transmigration by other Indonesians into the region.[27] Since the 1960s, consistent reports have filtered out of the territory of government suppression and terrorism, including murder, political assassination, imprisonment, torture, and aerial bombardments. The Indonesian government disbanded the New Guinea Council and forbade the use of the West Papua flag or the singing of the national anthem. There has been resistance to Indonesian integration and occupation, both through civil disobedience (such as Morning Star flag raising ceremonies) and via the formation of the Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM, or Free Papua Movement) in 1965. The movement's military arm is the TPN, or Liberation Army of Free Papua. Estimates vary on the death toll, with wild variation in the number claimed dead. A Sydney University academic has estimated more than 100,000 Papuans, one sixteenth of the population, have died as a result of government-sponsored violence against West Papuans,[28] while others had previously specified much higher death tolls.[29]

After General Suharto replaced Sukarno as President of Indonesia, Freeport Sulphur was the first foreign company awarded a mining license, a 30 year license to mine the Tembagapura region of Papua for gold and copper. In 1971, construction of the world's largest copper and gold mine (also the world's largest open-cut mine) began. Under an Indonesian agreement signed in 1967 (two years before the "Act of Free Choice"), the US company Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. obtained a 30-year exclusive mining license from Suharto in (dating from the mine's opening in 1973). The pact was extended in 1991 by another 30 years. After 1988 with the opening of the Grasberg mine it became the biggest gold mine and lowest extraction-price copper mine in the world. Locals made several violent attempts to dissuade the mine owners, including sabotage of a pipeline that July, but order was quickly restored.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Indonesian state accelerated its transmigration program, under which tens of thousands of Javanese and Sumatran migrants were resettled to Papua. Prior to Indonesian rule, the non-indigenous Asian population was estimated at 16,600; while the Papuan population were a mix of Roman Catholics, Protestants and animists following tribal religions.[30] Critics suspect that the transmigration program's purpose was to tip the balance of the province's population from the heavily Melanesian Papuans toward western Indonesians, thus further consolidating Indonesian control. The transmigration program officially ended in the late 1990s, although so-called "spontaneous migration" by western Indonesians voluntarily relocating to provinces such as Papua seeking economic opportunity has increased and remains at high levels.

A separatist congress in 2000 again calling for independence resulted in a military crackdown on independence supporters. In 2001, a now-majority Islamic population was given limited autonomy. An August 2001 US State Department travel warning advised "all travel by US and other foreign government officials to Aceh, Papua and the Moluccas (provinces of North Maluku and Maluku) has been restricted by the Indonesian government".

During the Abdurrahman Wahid administration in 2000, Papua gained a "Special Autonomy" status, an attempted political compromise between separatists and the central government that has weak support within the Jakarta government. Despite lack of political will of politicians in Jakarta to proceed with real implementation of the Special Autonomy, which is stipulated by law, the region was divided into two provinces: the province of Papua and the province of West Papua, based on a Presidential Instruction in January 2001, soon after President Wahid was impeached by the Parliament and replaced by Vice President Megawati Sukarnoputri. The division of the province has neither directly cancelled the Law of Special Autonomy of Papua nor engaged ongoing protest in the region. There was consideration of dividing the territory into thirds, but the plan was quickly abandoned. The plan again gained support in early 2008.

In January 2006, 43 refugees in a traditional canoe landed on the coast of Australia with a banner stating the Indonesian military was carrying out a genocide in Papua. They were transported to an Australian immigration detention facility on Christmas Island, 2,600 km (1,400 nmi) north-west of Perth, and 360 km (190 nmi) south of the western head of Java. On 23 March 2006, the Australian government granted temporary protection visas to 42 of the 43 having determined all 43 were bonafide refugees.[31] A day later Indonesia recalled its ambassador to Australia.[32] A number of expatriate Papuans currently campaign for independence in Australia, the United Kingdom and other countries, and call for international support for their campaigns. Their claims, which sometimes include allegations of historic or present genocide, are strongly challenged by Indonesia, and Papuan independence is not supported by any recognised government except that of Vanuatu.

International Parliamentarians for West Papua

On 15 October 2008, the International Parliamentarians for West Papua was launched at the Houses of Parliament, London.[33] The group was set up by exiled West Papuan independence leader Benny Wenda, and is chaired by the British MP Andrew Smith and Lord Harries. The group set out aims to develop international parliamentary support for West Papuan self-determination, through "recognising the inalienable right of the indigenous people of West Papua to self-determination, which was violated in the 1969 "Act of Free Choice".[34] Some of the founding members of the group were also involved in a similar group that was set up for East Timor prior to it gaining independence from Indonesia. So far the group has gathered support from politicians in countries including the United Kingdom, The United States of America, Australia, Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea.[35]

Administration

The region consists of 27 regencies (kabupaten), 2 cities (kotamadya), 117 subdistricts (kecamatan), 66 kelurahan, and 830 villages (desa).

The Regencies in Papua Province are: Asmat, Biak Numfor, Boven Digoel, Jayapura, Kota Jayapura, Jayawijaya, Keerom, Mappi, Merauke, Mimika, Nabire, Paniai, Pegunungan Bintang, Puncak Jaya, Sarmi, Supiori, Tolikara, Waropen, Yahukimo, and Yapen Waropen.

The Regencies in West Papua province are: Fak-Fak, Kaimana, Manokwari, Raja Ampat, Sorong, Kota Sorong, Sorong Selatan, Teluk Bintuni, and Teluk Wondama.

The city of Jayapura, is the largest city in West Papua. It is built on a slope overlooking a bay. Cenderawasih University campus houses the Jayapura Museum. Tanjung Ria beach, well-known to the Allies during World War II, is a holiday resort with facilities for water sports, and General Douglas MacArthur's World War II quarters are still intact.

See also

- Human rights in western New Guinea

- Postage Stamps of West Irian

References

- Leith, Denise. 2002. The Politics of Power: Freeport in Suharto's Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2566-7

- Conboy, Ken. 2003. Kopassus. Equinox Publishing, Jakarta Indonesia. ISBN 979-95898-8-6

- Online documentaries on the West Papuan struggle for independence, sponsored by West German-based Friends of Peoples Close to Nature

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gillespie, Richard (2002). (fullttext) "Dating the First Australians". pp. 455–72. http://www-personal.une.edu.au/~pbrown3/Gillespie02.pdf (fullttext). Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Free West Papua Campaign freewestpapua.org; aljazeera.net; "IPWP launched in UK Parliament". http://ipwp.org.

- ↑ US Dept of Defence; International Crisis Group; International Crisis Group

- ↑ The Economist

- ↑ (Whitten (1992), p. 182

- ↑ Robin McDowell: 'Lost world' yields exotic new species – The Vancouver Sun – 8 February 2006

- ↑ Grasberg MineSite | InfoMine

- ↑ Survival International – Papua

- ↑ Kayser M, Brauer S, Weiss G, Schiefenho¨vel W, Underhill P, Shen P, Oefner P, Tommaseo-Ponzetta M, Stoneking (2003) Reduced Y-Chromosome, but Not Mitochondrial DNA, Diversity in Human Populations from West New Guinea Am J Hum Genet 72:281–302

- ↑ "Ongoing Adaptive Evolution of ASPM, a Brain Size Determinant in Homo sapiens", Science, 9 September 2005: Vol. 309. no. 5741, pp. 1720–1722.

- ↑ Murray P. Cox and Marta Mirazón Lahr, "Y-Chromosome Diversity Is Inversely Associated With Language Affiliation in Paired Austronesian- and Papuan-Speaking Communities from Solomon Islands," American Journal of Human Biology 18:35–50 (2006)

- ↑ The exile who fights for the rights of all Papuans – By Martin Flanagan, The Age – 27 February 2003

- ↑ Letter to the Editor: "Papua culture is not at risk." – The Age, 3 March 2003

- ↑ United Nations General Assembly Resolution 448(V)

- ↑ McDonald (1980), p. 65

- ↑ McDonald (1980), p. 64.

- ↑ Vickers (2005), p. 139

- ↑ Friend (2003), pp. 76-77

- ↑ McDonald, Hamish (28 January 2008). "No End to Ambition". Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/no-end-to-ambition/2008/01/27/1201368944638.html.

- ↑ Conboy, Ken. 2003. Kopassus. Equinox Publishing, Jakarta Indonesia. ISBN 979-95898-8-6;McDonald, Hamish (1980). Suharto's Indonesia. Blackburn, Victoria: Fontana Books. pp. 36. ISBN 0-00-635721-0.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 McDonald, Hamish (1980). Suharto's Indonesia. Blackburn, Victoria: Fontana Books. pp. 36. ISBN 0-00-635721-0.

- ↑ Friend (2003), p. 77

- ↑ US Foreign Relations, 1961–63, Vol XXIII, Southeast Asia.

- ↑ US President letter.

- ↑ Friend (2003), p. 72

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Friend (2003), pp. 272-273

- ↑ Ricklefs, M. C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1300, Second Edition. MacMillan. p. 309. ISBN 0-333-57689-X.

- ↑ Report claims secret genocide in Indonesia – University of Sydney

- ↑ West Papua Support

- ↑ Report on Netherlands New Guinea for the Year 1961, Appendix

- ↑ Papua refugees get Australia visa – BBC News – 23 March 2006.

- ↑ Indonesia recalls Australia envoy – BBC News – 24 March 2006.

- ↑ "Launch of IPWP". International Parliamentarians for West Papua. 15 October 2008. http://ipwp.org/documents.html. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ↑ "Mission statement of IPWP". International Parliamentarians for West Papua. 15 October 2008. http://ipwp.org. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ↑ "List of politicians who support IPWP". International Parliamentarians for West Papua. 15 October 2008. http://ipwp.org. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

Further reading

- Penders, C.L.M., The West New Guinea debacle. Dutch decolonisation and Indonesia 1945–1962, Leiden 2002, KITLV

- "Arrow Against the Wind." Narrative of documentary on people of Asmat and Dani, their culture, and their relationship with the nature http://www.dgmoen.net/video_trans/004.html